Justin Trudeau to apologize for Canada’s 1914 decision to turn away steamship carrying 376 migrants

By Amy Husser, CBC News

It’s an apology more than a century in the making.

Nearly 102 years after the Komagata Maru sailed into Vancouver, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has offered a full apology in the House of Commons for the government of the day’s decision to turn away the ship, which was carrying hundreds of South Asian immigrants, most of whom were Sikhs.

The Komagata Maru arrived on Canada’s West Coast on May 23, 1914, anchoring in Vancouver’s Coal Harbour. Nearly all of the 376 passengers were denied entry and the ship sat in the harbour for two months. It was ultimately forced to return to India and was met by British soldiers. Twenty passengers were killed and others jailed following an ensuing riot.

“As a nation, we should never forget the prejudice suffered by the Sikh community at the hands of the Canadian government of the day. We should not and we will not.”

Here’s a closer look at what the prime minister described as a “dark chapter” in our history:

Setting sail

The Komagata Maru was a Japanese steamship chartered by wealthy Sikh businessman, Gurdit Singh, who was then living in Hong Kong. Its passage was a direct challenge to Canada’s immigration rules, which had grown increasingly strict — and discriminatory — at the turn of the century.

Canada needed immigrants to cultivate western farmland but preferred those from the U.S, Britain or northern Europe.

India had been a British colony for almost 200 years at this point, and Singh believed British citizens should be able to freely visit any country in the Commonwealth.

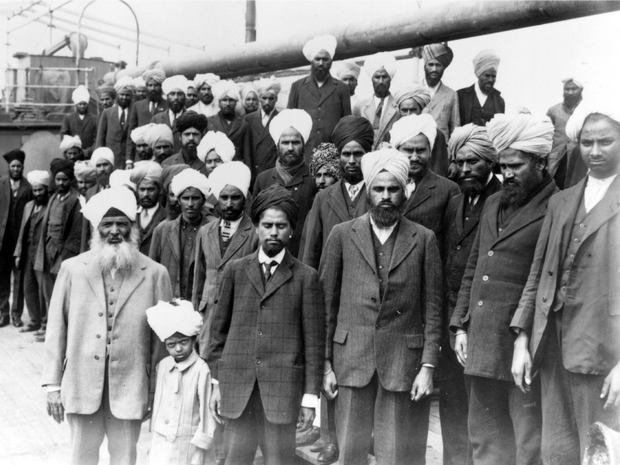

Passengers from the Komagata Maru, shown in 1914. (James L. Quiney/City of Vancouver Archives)

The steamship departed Hong Kong on April 4, 1914, making stops in Shanghai and Japan. Previously used to transport coal, the Komagata Maru had been transformed for the long journey.

Word of the ship’s intended destination quickly reached Vancouver, where anti-Asian sentiment was already in full swing. Local newspaper headlines of the day decried its arrival as a “Hindu invasion.”

In Vancouver, the Komagata Maru was immediately greeted by immigration officials who refused to let its passengers disembark. Twenty people determined to be returning residents were eventually permitted entry, but no one else stepped foot off the boat.

Why was it stopped?

“The reality is Canada kept all kinds of people out,” says Hugh Johnston, a retired Simon Fraser University history professor who wrote The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada’s Colour Bar. “Up until the 1960s, it was very hard for people from outside of northern Europe and the United States to come to Canada.”

By the early 1900s, British Columbia was home to about 2,000 Indians, mainly Punjabi Sikhs, who had come for work. They were some of the first Asian immigrants.

Canada instituted the Chinese Immigration Act in 1885, which included a head tax, to try to limit arrivals from the East Asian country.

By 1907, race riots and “anti-Asiatic” parades were taking place, spurred by fears that immigration would allow Asia’s large population to overrun Canada’s West Coast.

The Komagata Maru sits in Vancouver’s Coal Harbour in 1914. The ship became a spectacle for locals during its two-month stay at the waterfront.

British Columbians, Johnston says, were “very aware” of the established South Asian population. “They were more excited about this than the numbers warranted,” he says. “Ignorance about India would have been colossal.”

In response, Canada passed the Continuous Passage Act in 1908, requiring all immigrants to arrive directly from their point of origin, with no stops in between — a near-impossible task for those travelling from South Asia.

Immigrants from this region also needed to arrive with $200 in landing money, not dissimilar to rules still in place today intended to ensure new arrivals can support themselves, but fees back then varied from one population to the next.

In chartering the Komagata Maru, Singh was testing these new rules, though he may not have shared his strategy with his passengers. And as British subjects, they didn’t believe they were subject to the $200 landing fee.

These laws remained on the books until 1947.

Ship’s retreat

During the two months the Komagata Maru sat in the harbour, the ship became a spectacle, with near-daily newspaper reports of developments and crowds of hundreds gathering at the waterfront to gawk.

The Komagata Maru was formally ordered out in July. On the 19th, 125 Vancouver police officers and 35 special immigration agents attempted to board the vessel but were beaten back.

Four days later, on July 23, under the guns of the naval cruiser HMCS Rainbow, the Komagata Maru was escorted out to sea and began the journey to Calcutta.

Calls for an apology

Johnston began researching his book in the late 1970s, only a few years after Canada opened up its immigration policies, and says very few people had heard of the Komagata Maru at that time.

Justin Trudeau speaks to a supporter at the 20th Annual Mela Gadri Babian Da Sikh cultural festival in Surrey, B.C., on Aug. 2, 2015. The Liberal leader promised a formal apology for the Komagata Maru incident at that time. (REUTERS/Ben Nelms)

But Canada’s South Asian population now sits at 1.6 million, according to the 2011 Census, with India being the third most-common source country for recent immigrants.

“The consciousness has come as the number of South Asians in this country has increased,” Johnston says. “I know people who have [come] to Canada in the last 10 or 15 years and had no knowledge of this story. Then they find out about it and inevitably … are immensely disappointed that this is in Canada’s past.”

The Prof. Mohan Singh Memorial Foundation, founded in 1990, has been lobbying for an apology for nearly 25 years, working with local, provincial and federal politicians.

The importance of an official apology, group spokesman Herman Thind says, is “rooted in fairness.”

2008 apology

In 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney formally apologized to those sent to Japanese internment camps in the 1940s, and Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued official apologies for the Chinese head tax in 2006 and to residential school survivors in 2008.

The B.C. government formally apologized for the Komagata Maru incident in May 2008 and a monument was unveiled on Vancouver’s seawall in 2012, funded by the federal government.

But Harper stopped short of a formal apology in August 2008, when he instead apologized at a Sikh gathering of 8,000 in Surrey, B.C., home of the country’s largest Indo-Canadian population.

Stephen Harper speaks at the 13th Annual Mela Gadri Babian Da in Surrey, B.C., on Aug. 3, 2008, when he apologized for the Komagata Maru incident. Many attendees roundly rejected the apology, saying it should have been made in the Commons. (Darryl Dyck/Canadian Press)

Many in attendance immediately rejected the apology, saying it needed to be done on the floor of the House of Commons. The Prof. Mohan Singh Memorial Foundation, which organized Harper’s appearance, had made it “very clear” only a formal apology would be acceptable, Thind says.

“It’s always been about having an official apology written into Hansard so that it is on the public record,” he adds. “To us, that just amounted to a political statement made in an election year.”

The Liberals have been pushing for a formal apology for years and Trudeau made pre-election promises to do so in both 2014 and 2015.

Thind says his organization expects tomorrow to be a “huge celebration” with 500 people in attendance. The group, meanwhile, will continue to push for the Komagata Maru story to be included in Canadian curricula.

“If we’re to call ourselves a multicultural land, not a melting pot, then we really need to have a discussion about some of the struggles that other cultures had in coming to Canada.”

With files from the Canadian Press