An Alberta restaurant worker from Pakistan has been ordered out of Canada after facial recognition software analyzed his driver’s license photo and declared he is really someone else entirely.

While Farhan Mahmood says it is a bizarre case of two men with the same face, Canada Border Services Agency says its use of biometric technology caught a man who shouldn’t be in Canada.

It is among the first reported cases of CBSA proactively using facial recognition data to probe immigrant status although the technology has been a priority interest for the agency for years.

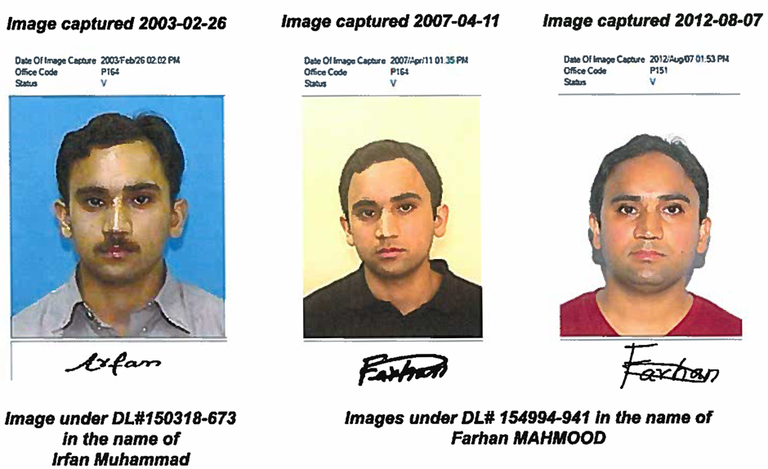

CBSA says Farhan Mahmood, 38, and Muhammad Irfan, 39, are the same person — in the flesh but not on paper.

Irfan came to Canada from Pakistan in 2003 and was refused a work permit that year and again in 2004. Immigration records show he left Canada on Sept. 23, 2003.

Although Irfan didn’t get a work permit, he did get an Alberta driver’s license on Feb. 26, 2003, a process that included having his photo taken.

Mahmood says he first came to Canada from Pakistan on Nov. 13, 2005, and obtained a work permit that year.

Even to an untrained eye the Irfan image and Mahmood images have striking similarities.

On April 11, 2007, Mahmood walked into the same Edmonton service office and had his photo taken for his driver’s license. Both photos were entered into the Alberta Motor Vehicle System called MOVES.

Mahmood and Irfan both applied for a permit to work at the same restaurant owned by Tariq Chaudhry, who sponsored both applications.

In 2014, Mahmood filed a lawsuit against Chaudhry alleging abusive labour practices. The split between the two was acrimonious and shortly after the lawsuit was filed, Chaudhry reported to CBSA that Mahmood’s real name was Irfan.

Regardless of the motive behind Chaudhry’s tip, CBSA investigated Mahmood’s identity.

Irfan’s 2003 driver’s license photo was run through the Alberta MOVES database: the system flagged Mahmood’s 2007 driver’s license photo as a 100% match and his 2012 photo as an 82.5% match.

At the request of CBSA, Gord Bryant, supervisor of Alberta’s facial recognition unit, did a manual comparison as well. He concluded the photos are “the strongest possible match.”

CBSA sought to have Mahmood kicked out of Canada on the grounds he misrepresented himself.

It wasn’t easy for the various checks and balances in the system to decide what to do with him.

He continuously denied he is Irfan — or that Irfan is him — and denied previously entering Canada using that name.

Last year, the Immigration and Refugee Board heard from Mahmood and Chaudhry, the spiteful tipster, as well as CBSA at a hearing.

Mahmood said he was in Pakistan, not Canada, in 2003: he got married on Feb. 14, 2003, to Rizwana Kausar and their daughter was born on Dec 17, 2003. But he provided little documentation to prove it.

Chaudhry’s evidence was described in court as “combative and self-serving and lacking credibility in many areas.” Although his words were given little weight, his tip was deemed accurate.

“Even to an untrained eye the Irfan image and Mahmood images have striking similarities,” said George Pemberton, the IRB adjudicator, in his decision.

Pemberton agreed Mahmood and Irfan were the same person, however, he did not declare him inadmissible to Canada because there was no evidence he had ever been asked if he had previously been denied a work permit.

The government’s appeal to the IRB’s appeal division brought a different ruling, finding there was adequate reason to consider Mahmood inadmissible.

Mahood then appealed to the Federal Court, which settled the matter in a decision released last week. Justice Glennys McVeigh dismissed his appeal.

Immigration and Refugee BoardImages from the facial recognition report the government used to determine that Farhan Mahmood and Muhammad Irfan are the same person.

CBSA is increasingly using facial recognition analysis to root out duplicitous duplicates. It is usually touted as a way to catch terrorists, gangsters and human smugglers.

CBSA this year planned to test facial recognition technology through a live video feed to match travellers against a database of previously deported persons in an operational border context, according to a Privacy Impact Assessment the agency filed.

In a 2014 facial recognition pilot project, CBSA ran 1,000 photos of wanted fugitives through databases. The test found matches for 15 who had alternate identities, Canadian Press reported.

In a few previous cases, facial recognition checks have led to immigration charges or removals from Canada of foreign nationals, including a Turkish man who applied for status as a Syrian refugee, but the published cases show the searches were initiated by other government agencies.

In this case, CBSA requested the search of Alberta’s database and caught a cook.

Mahmood’s lawyer, Martin Stoyanov, said he wouldn’t recommend that his client speak with the media about his case.

Requests to CBSA for information on its use of facial recognition went unanswered prior to deadline.